For this final installment of this series on my journey with grief, I’d like to focus on two themes. Since Kim passed, I have been aware of and navigating my way through these, but they have not fit into a specific chronological time frame. So here we go. Resiliency. In the epilogue of my book, Big Breath In, which I rewrote after Kim had passed away, I said that my resiliency was “running low these days.” Well, I admit to you now, that this was, in fact, not entirely true. My resiliency is, in fact, not “running low these days,” it is actually nonexistent (I felt I had to provide some hope at the end of the book). I have always prided myself on being able to function well under pressure. I’ve always been attracted to areas of leadership in crisis, being able to lead and act in a calm and reassuring way even when the present was in chaos and the future uncertain. It is what attracted me to hospital chaplaincy work and other leadership areas in which I have worked and volunteered. However, as I mention at the end of my book, after living through the loss of my brother Warren, the effects of respiratory failure due to Cystic Fibrosis, waiting for and receiving a double-lung transplant, walking with and caring for Kim for the past five years, and then, of course, the grief over losing her, I admit that my resiliency has run out. I feel like I have no backing to hold me up so that when any challenge comes my way, I simply fall over. Something as simple as a machinery breakdown on the farm has had me walking away from work and simply going home (my family has become very understanding of my antics). The slightest drop in my daily lung function test has had me canceling appointments, commitments, and work for a week or two. My lack of resiliency has led me to be panicked at the slightest setback or confusion. Now, there have been moments when I've felt that a fragile wall has been built behind me, something to prop me up so that when a challenge or hardship comes my way, I can feel myself rebounding back a little. However, that doesn’t last long. If any negative pressure or challenging situation is not resolved quickly, it is game over, and I am back to my huddled position at home. It appears that the person who used to thrive in times of crisis, who prided himself on being able to take on burden after burden, is finally burnt out. I wonder if resiliency is like trust, that once broken, it takes a very long time to build back, and maybe it never truly comes back as strong as it once was. But perhaps resiliency isn’t the key either. If resiliency implies returning to the original shape, I know that is impossible. Maybe it is not resiliency I should focus on, but transformation. I know there is no returning to who I was; there can only be transformation into who is now taking shape in me. I'll have to think about that some more.  Waiting Whenever someone is reading my book, and they message me that they found a particular part of it meaningful or funny, I right away go and reread that section (I think this has to do with some sort of insecurity within me or something). I was recently rereading a paragraph about my waiting for transplant, and I was struck by how similar my experience of grief has been to that time of waiting. During my wait for transplant, I was simply waiting. There was nothing I could do to speed the transplant process along; it would take as long as it was going to take. That was it. The same goes for grief. I often feel like I am just waiting for my sorrow to lighten up over time. I am waiting, putting in the time. Grief is going to take its time. It will never entirely pass, but I know the day will come (and I have had glimmers of that already) when it won’t be so paralyzing, when it isn’t so impactful and painful, and when I will begin to feel like myself again, or a new self. But until that naturally begins to unfold and reveal itself to me, I am simply waiting. It will happen when it happens. In his book, Lament for a Son, Nicholas Wolterstorff writes, “I have no explanation. I can do nothing else than endure in the face of this deepest and most painful of mysteries ... My wound is an unanswered question.” I find that word, endure, to be one of the most powerful words I have come across since Kim passed away. ENDURE. There is both a strength and a weakness to it. The “weakness” has to do with an inability to move forward freely. The power to rise is missing. But it is also a word of strength, of standing and looking into the face of the storm, allowing the blows of life to hit and to just try and withstand it. I have this picture in my head of standing still, allowing the sting of the rain and the whipping of the wind to hit me, of not moving forward, but also trying not to allow it to push me back or topple me over; to simply endure. That, I feel, is what life has become right now. I am in this time of sorrowful waiting, of needing to endure. It is not endurance or perseverance, for me, those words have this idea of running or moving forward––that is not it. Endure––like a rock––to stand and wait against the wind.  My View Today Getting this final blog post written has been a struggle (I'm not even all that happy with it, I feel it is missing the mark somehow). To use a quote from C.S. Lewis from last week, “all the hells of young grief have opened again.” Over the past week, I have felt a bit of a funk settling in. I’ve been feeling restless. This past tuesday evening, I was lying on the couch watching TV when someone rang my doorbell. I opened the door and recognized one of my neighbours, who also attends the church I’ve started going to since the summer, standing there holding a gift basket. She said that one of the things the church does every Christmas is hand out gift baskets to those in the congregation who have recently gone through a profound loss in their life. Standing at the door, receiving the basket, I felt a lump forming in my throat. As I closed the door and placed the basket on the counter, I lost it. I couldn’t stop crying for about ninety minutes. It was the straw that broke the camel’s back. Currently, the bombers are back. My wooden leg is kicked out from under me. The shine of the last seven weeks has worn off. “All the hells of young grief have returned.” I am thankful for the positive season I had this fall. It has allowed me to process a lot of my grief and write this series. But it seems as if on cue, with the closing of this series, so are the curtains closing on the light that was shining in. It feels different than October and not as bad. I have learned things I can do to not return to that place, but grief is unpredictable, and at least right now, it’s not easy.

So, there you have it—my journey with grief over the past eight months. I hope to return to this blog series in the spring to update you on how things are going, but for now, I will begin using this blog for other things. I hope to continue to write here and give updates on my book and more on the world of CF and transplantation. I have some ideas rolling around in my head that could be fun, but those will have to wait for the new year. Thanks for reading and following along thus far.

0 Comments

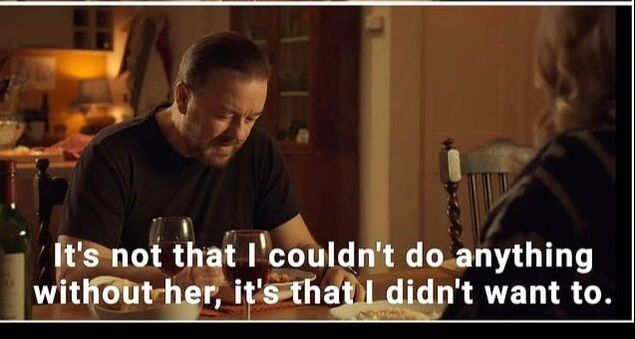

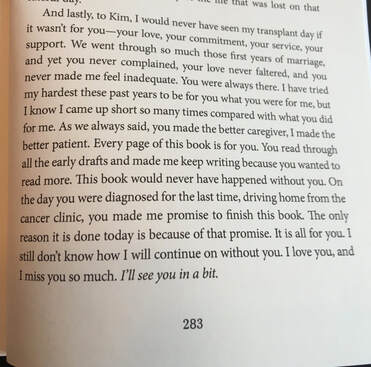

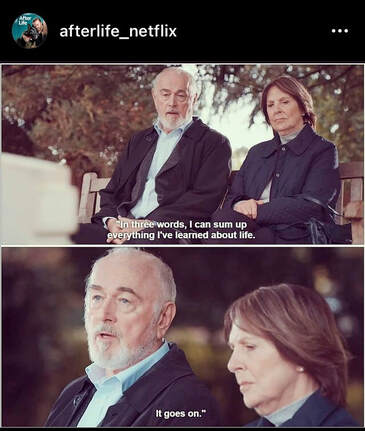

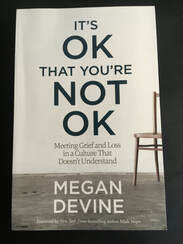

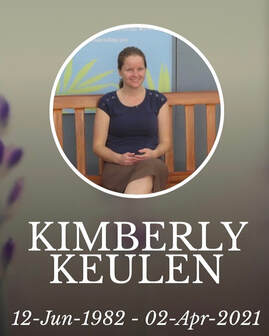

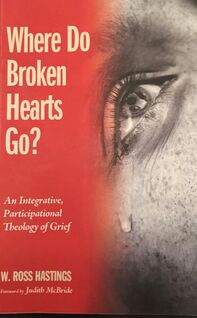

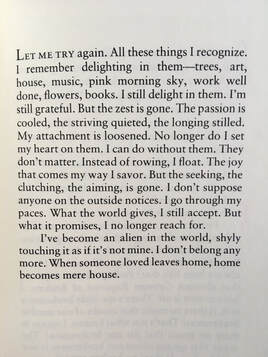

If one thing has understood my grief or best reflected my experience of grief since Kim passed, it has been the Netflix show, After Life. My good friend Leann recommended the show to me about a month after Kim’s passing. The main character, Tony, played by Ricky Gervais, has recently lost his wife to cancer and is now trying to navigate life. The show has some crude language and humour (Ricky Gervais is the writer, after all), but for me, the writing of the show, and Gervais' acting, has resonated so deeply with my own experience. At the end of the first season, however, I got worried. Tony, the widower, was beginning to show positive signs. He seemed to be emerging out of the darkness and grief that marked the show's first five episodes. I was worried this would be like every other show about grief or loss, and this was going to be the start of a trajectory of recovery and happily ever after. But when I apprehensively began episode one of season two, I was met with a surprise. Tony was once again down in the dumps and had slid back down the snake of grief.  C.S. Lewis (author of the Narnia series) wrote a book entitled, A Grief Observed. It is about his experience of grief after losing his wife to cancer. In it, he writes, “Grief is like a bomber circling round and dropping its bombs each time the circle brings it over-head; physical pain is like the steady barrage on a trench in World War One, hours of it with no let-up for a moment.” Having lived in England for both World Wars, I trust he knows what he is talking about. But this is what grief is like; one moment, the bombers are overhead dropping their bombs, and you don’t know how you will ever survive the barrage of chaos. And the next moment, the sky is clear, and you can come out into the sun. Sometimes the cycle of dread and relief is tight; other times, it is wide. For me, as the month of October began winding down, the grief-bombing of that month began to let up. A simple event happened that lifted the ceiling on my grief and allowed me room to reflect and remember.  Kim always enjoyed spreading manure with me. Kim always enjoyed spreading manure with me. For environmental reasons, dairy farmers are not supposed to spread manure on their fields from November to February here in the Lower Mainland. Therefore, the goal is always to get the pits empty by the end of October. One of my jobs on the farm is spreading manure, and I love it. There is nothing like looking at a field plastered with manure at the end of the day to make you feel like you’ve done something. As everyone knows, this fall, we have seen a torrential amount of rain, beginning already in September. So, when we had two days of nice weather near the end of October this was the chance we needed to empty the last bit of manure from our pit. And in regards to some of my depression, this was the first light in the darkness--grief is that strange. Spending two days in the tractor, hauling 33 loads of manure (148,500 gallons); the empowerment of feeling the weight of 4500 gallons of shit sloshing around behind me with each load, feeling the horsepower and torque of the tractor under my feet; it was just enough to lift the fog, distract my mind, give me a sense of joy, and get me onto some solid ground. With this crack in the door, other dominos began to fall. A couple of days after emptying the pit, I was at home rereading one of my favorite book on spirituality, New Seeds of Contemplation, by Thomas Merton. I came across a sentence that I had earlier underlined: “Why should joy excite me or sorrow cast me down, achievement delight me or failure depress me, life attract or death repel me if I live only in the Life that is within me by God’s gift.”  What struck me while reading this quote was not its subject matter. Instead, while reading this sentence, I remembered a conversation that Kim and I had a couple of times. The crux of this discussion, or Kim’s expressed desire in those conversations, was that she did not want me to become depressed or sad after she was gone. What grieved Kim the most in her final months was not so much her own death but what it would do to me and others. She didn’t want me to live in the paralyzing fog and sorrow that I indeed found myself in for much of October. For some reason, reading that sentence by Thomas Merton woke me up to the fact that Kim would be heartbroken and most likely a bit angry if she knew how I had been doing since her memorial. I realized that this was no way to honor her. By not seeking to come out from under the depressive fog I was lost in, I was, in a sense, re-enacting her death all over again. Now, it wasn’t like this was a miracle-fix or anything, but again, it was something that helped lift the clouds a bit more and made me take another step in trying to find a way through this grief. There was now the incentive to honor Kim with my life going forward. The next domino fell two days later, on a Sunday afternoon. I went for a short walk along the Nicomekel River in South Surrey. I was contemplating my mood and season of grief, wanting to find a way through. During that thirty minutes in the cold wind, I decided that I needed to get busy. I had to begin filling my time with routine and work (anyone who has read my book will know I like routine).  I also realized I couldn’t hit my grief head-on. I believe there are times when we need to face our grief and sorrow face-to-face. To look it in the eye and feel the total weight of its powerful blow, to let it break us so that we can begin to put the pieces back together. But having done this a couple of times, I also began to see that to survive, I had to start hitting it from an angle. I had attempted several times to catch grief out on the open ice, line it up in the trolley tracks and take it down. Though this worked in the summer while I was in shock, I was now feeling the full pain of these head-on collisions. In taking on my grief from an angle, I could make contact, deal and wrestle with it for a bit (such as writing these blog posts), and then spin off and get busy with something else when I felt the balance of power shifting against me, when it became too much. Throughout the following couple of weeks, now transitioning into November, I also did some work for my close friend, Garrit, who owns his own contracting business. There is nothing like spending a day shoveling dirt, carrying drywall, or loading a tonne of broken concrete into the back of a trailer to help get those mind-cleansing endorphins going. I began setting up a schedule for my week, with specific days on the farm and certain days at home, writing or spending time volunteering in the CF community.  Another domino to fall was the release of my book in early November. As I outlined in the previous blog post, the book's release was a cause of pain, but the reception it got in terms of how well it sold was very heartwarming. To see it hit the FriesenPress and Amazon bestseller list on its first weekend was incredible.  I wished so badly that Kim could see it, but I also can’t discount the boost of self-confidence it gave me. And the texts and social media feedback I have received since has been overwhelming. So, where am I at then today? Well, let me begin to bring this post to a close with another, rather lengthy quote, from C.S. Lewis in A Grief Observed: “Getting over it so soon? The words are ambiguous. To say the patient is getting over it after an operation for appendicitis is one thing; after he’s had his leg off it is quite another. After that operation either the wounded stump heals or the man dies. If it heals, the fierce, continuous pain will stop. Presently he’ll get back his strength and be able to stump about on his wooden leg. He has ‘got over it.’ But he will probably have recurrent pains in the stump all his life, and perhaps bad ones; and he will always be a one-legged man. There will be hardly any moment when he forgets it. Bathing, dressing, sitting down and getting up again, even lying in bed, will all be different. His whole life will be changed. All sorts of pleasures and activities that he once took for granted will have to be simply written off. Duties too. At present I am learning to get about on crutches. Perhaps I shall presently be given a wooden leg. But I shall never be biped again. “Still, there’s no denying that in some sense I ‘feel better', and with that comes at once a sort of shame, and a feeling that one is under a sort of obligation to cherish and foment and prolong one’s unhappiness. I’ve read about that in books, but I never dreamed I should feel it myself. I am sure [Kim] wouldn’t approve of it. She’d tell me not to be a fool... "For me at any rate the program is plain. I will turn to her as often as possible in gladness. I will even salute her with a laugh. The less I mourn her the nearer I seem to her. "An admirable program. Unfortunately, it can’t be carried out. Tonight, all the hells of young grief have opened again; the mad words, the bitter resentment, the fluttering stomach, the nightmare reality, the wallowed-in tears. For in grief nothing ‘stays put.’ Round and round. Everything repeats. Am I going in circles, or dare I hope I am on a spiral? But if a spiral, am I going up or down it... "The same leg is cut off time after time. The first plunge of the knife into the flesh is felt again and again. They say ‘The coward dies many times’; so does the beloved.” As I have written in earlier posts, I never realized until Kim was gone how much she propped me up, how much I depended on her for my confidence. She was the support and confidence of my life while we were together, and now, in her expressed desire to see me live a positive life, to not remain in the depth of sadness over her passing, she continues to be my support today. Even in her death, she is propping me up. Each night now, as I get into bed, I take her picture off my bedside table, hold it in my hands, and tell her about my day. It is in turning to her in gladness, and even some nights with humour, that I do feel closer to her. She supports me still.  Like Tony at the end of season 1 in the show After Life, the period I am in right now is a positive one. I have taken some steps and added some awareness of what I need in order to be in a better place emotionally and physically. I know another depressive season will one day hit. I still hear bombers in the distance coming around; I feel the frailness and pain of my "wooden leg," but I feel I am at least holding onto a ladder, ascending one slow rung at a time. This blog post then brings me up to the present day on my journey with grief. When I made the outline for this series of posts, I thought that my present-day would require a new post, separate from how I had been doing a couple of weeks ago when I started writing, but that is not the case. The positive season is holding for now. I will, however, write one more chapter before I break from this series. It will deal with a couple of themes that have run throughout my journey but haven’t fit within any specific chronological time frame. Thanks for reading and sticking with me thus far.  Netflix show: "After Life" Netflix show: "After Life"  Note: This chapter is a bit long and a bit rambly. Sorry. Sorrow, depression, grief––these are all disorientating experiences that often leave one feeling like they are swimming in a swamp of their own emotions and experiences. It has been difficult to force myself to sit down and write this chapter of my journey with grief because it has been challenging to try and process and organize these more recent emotions and experiences into something that a reader might understand. It is like trying to reconstruct a meal after you have just vomited it into the toilet. But here we go... To try and make sense of the six weeks following Kim’s memorial, specifically the month of October, I will try and compartmentalize this time into three topics or categories. What I am writing about here are emotions and experiences I've had since Kim passed, but I am placing them within the chronological time frame of October as they were all triggered and intensified within one week in early October. On Accomplishment On Oct. 8, the Friday before the Thanksgiving long weekend, I had a meeting with my publishing specialist. Among the things we discussed about my book, we decided to push the release date up to early November. There were a couple of reasons for this, one of them having to do with supply chain issues and making sure the book would come out and be available for shipping before Christmas. But it was quite a startling moment to realize that this journey of publishing my book would end within a month. And with that, as soon as I hung up the phone, a wave of sadness washed over me. Part of the letdown that I experienced is, I think, the same as what many people have after a big project is completed. You are pushing and pushing, focused on this one big thing, and then there is an emotional letdown once finished. It is as if our emotions have nowhere to focus anymore, and we begin to slip into this sad or dark place. But more than this for me, what especially tripped me up and sent me down this slope of depression, was the meaninglessness of the accomplishment that I felt. Without Kim to see and experience this with me, it felt empty. Now don’t get me wrong. I have been humbled and so incredibly appreciative of all the positive feedback for my book. It is the only thing that is now keeping me excited and proud of this project. But the joy, the excitement, the sense of accomplishment I expected to feel, was absent.  What kept me focused during the difficult early days of writing was Kim’s excitement and positive feedback to my early drafts. If you have read my book and read the very last page, you will know that when Kim was diagnosed for the final time, in August 2020, she made me promise to finish the book and to get it published. At that time, we had hoped we would have been able to do this together, but of course, that didn’t happen. Kim had a hand in editing my manuscript and giving her thoughts on the physical shape and design of the book, but she didn’t get to see any of the proofs. This sense of the emptiness of accomplishment was not new to me in October. Already in the summer, I shared with some people how it felt like nothing was worth doing if I couldn’t share it with Kim. Not until Kim was gone did I realize how much I enjoyed the things I did because I could share them and talk about them with Kim. Last week I met with my spiritual director and shared with him that I am not yet at the point where I can enjoy something just for the sake and dignity of it. I trust and hope I will one day get there, but still, now, my sense of accomplishment in life is attached to being able to share it with Kim. With her gone, my accomplishments don’t mean all that much. They are just a way to pass the time. I feel guilty for feeling this way, especially as it relates to my book. You, as my readers, have been purchasing my book and spending your money on it. Many of you are taking hours out of your life to read it, and I appreciate that so much! I don’t want to disrespect that. But when life changes so radically in the middle of an emotionally charged project, it’s hard to maintain the original spirit of accomplishment; it becomes tarnished. When I began writing, the dream I had was to do this with Kim. That dream is unfulfilled.  On Community Over the Thanksgiving weekend, a couple of people texted me, communicating their support and sorrow that a weekend so focused on the theme of gratitude must be difficult for me. That idea never actually really occurred to me until I got those texts. I’m not one for major holidays. I value the meaning behind them, but I'd rather focus on cultivating a spirit of thanksgiving throughout the year rather than artificially manufacturing it on one weekend. The same goes for Christmas. I like getting together with family, and that it feels special, but overall, whatever, I’m a bit of a scrooge. Therefore, I floated through the weekend without much thought to the contradiction of my grief and the weekend's theme of gratitude. All of this, however, left me unprepared for what did happen. My family got together the Sunday evening. We had a nice dinner, and we all had a good time. We finished up dessert, coffee, and drinks and were cleaning up. I then decided to make my exit. However, it was then that something I had done so many times before without too much thought or emotion hit me: I was going home alone. Now, of course, this was not the first time we had got together as a family since Kim died. And it had nothing to do with Thanksgiving. But that five-minute drive home served as a reminder and manifestation of just how lonely and empty my life, my future, felt. No matter where I went––family dinners, social outings, drinks with friends, work, or church––I was always coming home alone and walking into an empty house. It is as if the joy and laughs experienced during times of community, with family or friends, disappear into a vapour as soon as I get in my truck and the passenger door remains closed. When I leave the house for the evening, I always turn a light on so that at least there is some sense of warmth, of life, when I come home. But no matter how many lights I leave on or how good of a time I have when I am out, it can’t compete with the empty, silent house that awaits me. Often, which is a common thing for widowed people, when I come home from work, I will turn on Netflix or some music right away, and then I will go shower. I do this so that there is at least some noise in the house when I come back downstairs. Again, this wasn’t something new in October, and it is not always a painful experience to step into the house. Still, the grief about this reality was so much more profound, so much more depressing throughout October, especially on that Thanksgiving Sunday. And this leads me to my third categorization of the ever-deepening grief of that month. On Experience & Time Before these two experiences happened, another one actually set up the slide into the depression that I felt I was falling into for most of October. Since my transplant, I have been involved in advocacy work for Cystic Fibosis Canada, and for our local clinic here in Vancouver. During the summer, I decided to plug myself back into that advocacy work. Over the past couple of years, the big push in the CF world has been getting access to new medications coming online that are a real game-changer for people with CF, especially the latest one, Trikafta, a miracle drug for many people. The downside of these drugs is they are costly, therefore it takes a while for publicly funded healthcare systems to get on board with funding them. When I re-entered the world of advocacy this past summer, I joined in on the final push to get Canada and the province of BC to approve Trikafta and make it available for CF patients. To say that Oct. 5 was a milestone in CF care here in BC is an understatement, as this was the day that our provincial government approved Trikafta, thus changing the lives of hundreds of people here in BC. For me, however, this day came with mixed emotions. I was thrilled to be part of this final push to get this drug approved; I was happy for my CF peers, who can now have access to this drug, but for me, it comes too late, as being post-transplant, I do not qualify to be on it. On Oct. 6, there was a Facebook Live event to celebrate this momentous day, but I felt myself slipping into a pit as the meeting wound day. It was as if the bittersweet emotions of the day cracked open a dark door that was then quickly flung wide open by the realization that Kim would never know that this day in CF history happened. This idea and sorrow over Kim not knowing something was not new on that day. Already back in the spring, I came to the painful realization that everything that happens in life from here on out, Kim will not know about. Kim’s knowledge base, her experiences stopped on the day she died. I find it very painful that Kim doesn’t know what's happening in the world or in the life of those she loved. Kim doesn’t know about the heat dome or the wildfires of this past summer. She doesn’t know about the flooding and how it is affecting our family in Abbotsford. She doesn't know about the mundain ordinary things in life. She doesn’t know how my book is being received. And she doesn’t know what is going in the CF or transplant world, or even about my own health (which is fine). This idea is almost the most heartbreaking part of my grief, other than her not being here. Kim loved knowledge, and she loved to know what was going on with people, and she loved real-life stories. Learning and experiencing things she hasn't known or experienced is where I feel such a significant separation from her now. I continue to change, but she stays the same. The world keeps going; life goes on, but Kim stopped. I want to stop. I want to hold time back, tell others to stop, hold on, and not go any further without her, but that is impossible. Time can’t be stopped; whatever is coming will come, and whatever is past will continue to grow further and further into the past. These three events: the upcoming release of my book, leaving Thanksgiving dinner, and the approval of Trikafta, all happening in one week of each other, sent me into one of the darkest and most inconsolable times I've experienced over the past eight months. It was a time where I began to experience and understand things about depression that I never had before. I think I looked fine on the outside, and those closest to me might likely be surprised to read all this. But it was a time when I began to get scared that this darkness was what life was now going to hold for me. Hope had been shut out.

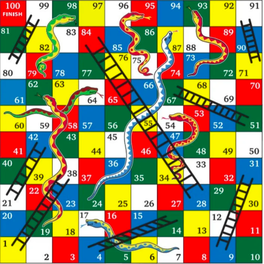

However, as unpredictable and quick as these moments of disorientation hit me in early October, so too was the unpredictability in which a ray of light began to scatter some of that darkness away. What brought on this next chapter of my journey with grief, you ask? Well, it might take a certain kind of person to understand it, but it was simply 148,500 gallons of shit (literally).  “Loss stuns us into a place beyond any language ... Language is a cover for that annihilating stillness, and a poor one at that.” (Megan Devine, It’s OK That You’re Not OK)  In the months leading up to Kim’s passing, Kim and I talked a couple of times about her memorial. We made a rough plan of what it might look like and who she would like to speak at it, and we talked about a couple of songs we would either sing or have played. We also talked about timing of the memorial, and that she wanted us to wait until after COVID was over so there wouldn’t be any restrictions on who could attend. Kim wanted everyone who wanted to attend to be able to do so. She was always thinking of others. When we made these plans, all signs pointed to COVID-19 being significantly weakened, if not in our rear-view mirror by the end of summer 2021. The vaccine was rolling out, and summer was coming. What we didn’t know was that the fourth-wave of COVID was also about to begin. As you now know, we were not able to honour all of Kim’s wishes. In August, when we met as a family to discuss plans for a memorial, we all felt that if Kim knew the current situation, that the Delta-Variant was now active and growing, and that it was most likely going to spread through schools once September hit, she would most likely have said, “OK, get it done already.” And so, with that, we went ahead and had Kim memorial on September 10th, with a limit of 200 people in attendance and COVID safety measures in place to ensure we did not become a spreader-event and to protect persons like myself. I mention all this as background to this next chapter of my grief. Because we waited five months to hold Kim’s memorial, I believe the experience of her memorial was much different than if we had held it within the first month. In the week leading up to Kim’s memorial, I felt a growing anxiety within me. Not only was I worried about how painful and difficult the actual event of Kim’s memorial would be, but there was something else happening, a feeling I couldn’t put into words. It felt as if a chapter of my life was coming to an end. With Kim’s memorial happening on a Friday night, I had this feeling that something was going to happen over the weekend, that there was an "opening," an abyss, that was about to engulf me. I felt as if I was coming to the edge of a cliff. I am so incredibly proud of Kim’s memorial. I am thankful to everyone who spoke and how they honoured Kim with their words and stories. Pastor Jenna Fabiano, who officiated, did such an excellent job as well. The musicians also brought such a peaceful atmosphere to the building. I was so grateful that Kim could be honoured in such a powerful way.  The rest of that weekend, however, just kind of slipped by. I worked on Saturday to try and keep my mind busy (we were in the middle of corn harvest). On Sunday, I stayed in my PJ’s all morning until I went to the farm in the afternoon to work again. But something happened on Monday morning. That thing I had felt inside of me, that change that I felt coming during the previous week, that anxiety, finally came to the surface. Monday, September 13th, was a bright and beautiful morning. I woke up at my regular time, had breakfast, did my lung function tests as I do every morning, and then decided to go for a walk. I was about three-hundred meters from my house, about to cross a street (I can picture it clearly in my mind), when all of a sudden, a phrase came into my head that stopped me dead in my tracks: Today is the first day of the rest of your life. That was it! That was what the growing anxiety, the suspicion of what Kim’s memorial would mean. A new chapter, a new life, was now beginning. But, whereas this phrase, the first day of the rest of your life, is often used in a positive or motivational fashion, this instance of it came with nothing but immense life-piercing sorrow. In the five months preceding the memorial, it still felt like I was somehow living with Kim. I don’t know if it was because of the shock that I wrote about in the previous post, if it was because her passing was still so fresh, or if it was because we had not yet had her memorial; but it felt like Kim was still with me somehow. The chapter had not yet ended. During the summer, I was still anticipating something with Kim. The symbolic book of our marriage, our journey together, had not yet finished. Throughout the spring and summer, there was still something to come that had to do with Kim, something I would still do for her, something that Kim would be part of, that she would be central in. Kim’s chapter had not yet ended. However, with her memorial, and the symbolic nature that memorial services often take on, it was as if the chapter was now closed; and now, on the following Monday morning, I was staring at a blank page. Nicholas Wolterstorff, in this book, Lament for a Son, writes, “Something is over. In the deepest levels of my existence something is finished, done. My life is divided into before and after.”  It was as if there was this open space, this empty silence in front of me. It felt like I was expected to move on, that any excuse of not making plans for the future, of finding stability, were now over. There was nothing to look forward to, no more ending point; there was now just a future without Kim. It felt like the chapter, whose title still included Kim’s name in it, was now done, and from here on out, the chapter titles would only have my own name. From this moment on, it felt as if Kim would now exist only in my memory. And each day after the memorial would feel as if I was moving further and further from her. Again, in this book, Lament for a Son, Wolterstorff writes, “It’s the neverness that is so painful. Never again to be here with us––never to sit with us at the table, never to travel with us, never to laugh with us, never to cry with us, never to embrace with us ... All the rest of our lives we must live without [her]. Only our deaths can stop the pain of [her] death. A month, a year, five years––with that I could live. But not this forever.” Here is something I just thought of in writing this (writing always helps me process things). The word “widowed” means “to be empty.” Since Kim's memorial, I have been saying that I have this sense of “openness” in front of me, but I always need to qualify that by saying it is not a good thing. It is like being unanchored in a storm or staring out the door of an airplane with no parachute. But maybe instead of saying I feel this sense of “openness,” I should say I feel a sense of “emptiness” in front of me. I know I feel empty inside. I feel like the shell of the man I was a year ago. But maybe that is also the word that best describes how I feel about the future: EMPTY.  I’ve used part of this quote in an earlier blog post, and I wasn’t planning on using it here, but I think it fits. Again, it is by Nicholas Wolterstorff: “Let me try again. All these things I recognize. I remember delighting in them––trees, art, house, music, pink morning sky, work well done, flowers, books. I still delight in them. I’m still grateful. But the zest is gone. The passion is cooled, the striving quieted, the longing stilled. My attachment is loosened. No longer do I set my heart on them. I can do without them. They don’t matter. Instead of rowing, I float. The joy that comes my way I savor. But the seeking, the clutching, the aiming is gone. I don’t suppose anyone on the outside notices. I go through my paces. What the world gives, I still accept. But what it promises, I no longer reach for. I’ve become an alien in the world, shyly touching it as if it’s not mine. I don’t belong anymore. When someone loved leaves home, home becomes mere house.” I think it felt like Kim had not entirely left before her memorial. But now that the memorial was over, I felt suspended. She is gone for good other than in my memory. Life got back to normal for everyone else, but my life (and those who loved her) would never be the same. I go through the motions of life, and I can find some enjoyment in them, but the big questions of life that matter are left empty; they are unanswered because I don’t know how to answer them. This chapter of discerning this sense of emptiness continues today. When I try to look ahead, it is still an abyss. However, the “purity” of this emptiness lasted only for a week or two after Kim’s memorial, as is was soon filled with a fog of depression. The season of grief that followed Kim’s memorial was maybe not as visceral and unpredictable as certain moments that preceded it in the spring and summer, but it was more profound and painful. As September turned into October, and even as good and exciting things began appearing on the horizon, I started slipping into a depression and fearfulness that I had never experienced before.  “The reality of grief is far different from what others see from the outside. There is pain in this world that you can’t be cheered of ... Some things cannot be fixed. They can only be carried.” (Megan Devine, It’s OK That You’re Not OK”) As I reflect on the past seven months without Kim, I see that what I might call a “first chapter” of my journey with grief happened during the spring and most of the summer of this year. There are two defining features that I see at play throughout that time. The first was shock; the second was a complete loss of identity. Shock. Back in May 2019, I broke my arm. I was mountain biking in Watershed Park, just minutes from my house. I was riding a downhill trail, one I had done many times before. I came to a tabletop jump whose landing went immediately into a sharp right-handed bend. I hit the jump fine, but in landing, my rear wheel hit the edge of the tabletop, which then ejected my bike forward straight into the high-side of the lefthand berm. My front tire hit this wall of dirt, and my bike and I went flying through the air, wheels over handlebar. While flipping over in the air, I remember thinking, “don’t worry, you’ll be okay, you’ve crashed hard before.” However, when I hit the ground and came to a stop (sitting upright), I noticed that I was covered in blood. I then looked at my right arm and saw that it was bent in a way it was not supposed to ever be bent, and there was a bone sticking out of it. In the three seconds it took to realize how much trouble I was in, I remember thinking, “Please, shock, do what you were made to do!”  Ross Hastings, a professor of mine at Regent College, and whose wife passed away from cancer in 2008, has written a book on grief, Where do Broken Hearts Go? In it, he writes, “For one thing, when a loved one dies, no matter how well prepared we think we are, we shut down in various ways and to different degrees. We are in shock ... Shock, our involuntary defence mechanism, is actually a gift.” Before reading these words in 2016, the same year that Kim was first diagnosed with stage-four colon cancer, I had always thought that shock was a bad thing, that it was somehow an escape from reality. A weakness or something that wasn’t the best way to process or move forward (to be sure, one cannot live in a state of perpetual physical shock; its symptoms can kill a person. When I broke my arm, I experienced many of those symptoms: drop in blood pressure, profuse sweating, skin turning grey or white). But what I didn’t understand before reading this book is that shock is actually a saving grace. Shock is a natural way for the body to survive, for short periods of time, immense life-threatening pain. Back in 2019, sitting beside a tree with a bone sticking out of my arm, shock is what gave me the survival instinct and ability to stand up (albeit on the edge of fainting) and walk/shuffle out of the forest so that the ambulance could pick me up and bring me to the hospital as fast as possible. In the same way, in the immediate days, weeks, and months after Kim passed away, shock was one of the main things that helped me survive what would have been insurmountable emotional pain. Sitting here today, most of the spring and summer is a blur to me. Most of my memories from just a few months ago are swallowed into an indistinguishable mass. There are things I know I did, people I met, family I spent time with, but the details are a fog. Meeting a friend at White Rock beach on several occasions to watch the sun go down and share memories of Kim. Having a close friend come over for drinks to check in on me. Getting together with Kim’s family, where one of Kim’s brothers made all of our drinks a little stronger than usual, thus helping dull the fact that Kim was so painfully missing. And, of course, putting in a lot of time working on the farm. But many of those memories are a blur. What was said, and the number of times they were repeated, is all lost. I was in survival mode. I knew I needed to talk to people, so I sought out friends, or they sought me out. I knew I needed to get out of the house, so I went for drives, walks, bike rides, or sat on the beach. But looking back, it is as if I was on autopilot and I wasn’t taking anything in. I was trying to survive until the following day, just putting in time. The shock prevented the pain of Kim’s absence from reaching the core of my being, but it also stopped everything else in life from penetrating as well. Now don’t get me wrong. In the weeks and months after Kim passed, there were moments of incredible pain. Times where I would be lying face down on the couch, pounding the pillows with everything I had, and expelling groans too deep for words. In those moments, I didn’t know how I was ever going to go on. There were times I wept openly in front of friends and family. Times I felt I couldn’t go on and didn’t want to go on. But despite those moments of complete disorientation, I was also able to function in ways that surprised me. It was as if the shock would let off a pressure release of grief so that I didn’t explode, but it also protected me from feeling the full impact so close to the event.  Kim and I attended Ross' book launch just months after Kim's initial diagnosis. He signed our copy appropriately. Kim and I attended Ross' book launch just months after Kim's initial diagnosis. He signed our copy appropriately. “With shock comes numbness and an unintentional sense of denial. Our minds cannot grasp it. Our emotions are too powerful to be processed at that time. If we did not have defence mechanisms in place, we would not be able to handle the reality of our losses. Their full impact would kill us.” (Ross Hastings, Where do Broken Hearts Go?)  This idea of being in shock was not something I was totally aware of at the time (at least, I don’t think I was). It was not until August began winding down and I entered into some deeper reflection that I realized how much my internal defense mechanisms had protected me during the first four months of being without Kim. Identity The second significant piece of my grief puzzle, however, had to do with my identity. One thing that I did feel within the first weeks after Kim’s passing was a total and complete loss of identity. In being married to Kim, we had created an identity together. We didn’t lose our individual identities to each other, we were still two very different people, but we had also come to create a new identity as one person. With Kim now being gone, it was as if half of me had been torn away. I felt like a building you might see on the news, where half of it has been bombed to rubble, and so each floor of the building ends in midair, and wires and pipes are sticking out into nothing. I felt like my identity had been cut in half, ripped apart. And with this came a total loss of confidence. I think I am a fairly courageous person. Through life experience, I have come to see that there is not a lot in life that we can have control over or hide from, and so it is often better to just hit difficult situations head-on. However, I am not a confident person. Never have been. As a kid, I would always get sick to my stomach before hockey games. I feel I am often timid in social settings where I don’t have a leadership role. But never has my lack of confidence been more acutely felt than now, without Kim. I didn’t realize it until she was gone, but I ran almost everything I did past her. Something as simple as what to wear to church when I was preaching; I would always come downstairs after showering and dressing, stand in front of Kim, and ask, “Is this okay?” Whenever I would purchase something (other than books), I would ask what she thought. We would often go for walks in the evening, sharing about our day, talking through all our decisions in life. I am an over-thinker, and so often, the only way I would make a big decision was when Kim would finally say, “Just do it already.”  With her gone, I now feel paralyzed and panicked. This summer, when I began making final edits and approvals for my book, I broke down. I had no clue if anything I was rewriting was any good, if it made sense, or even fit in my story. I had no clue how to pick the image and design for my front and back cover. I felt hollow. Thankfully, my sister-in-law, Heidi, who has a very keen eye for design and was excited to help with my book, walked me through the final half-year of publishing. I no longer knew who I was, what I liked, or what I wanted. I had lost my identity, I had lost all confidence. The final quote I will use from Ross Hastings' book is this: “I think grief is the process of shock thawing out.” Sitting on the side of 64th Avenue back in May 2019, a truck-load of firefighters standing around me, I knew that my shock was soon going to dissipate. Now that I was out of the woods, first responders present, my body was beginning to feel safer. The paramedics arrived within minutes. They wrapped my arm, got me onto the stretcher, and loaded me into the back of the bus. The driver closed the doors, walked around the side of the vehicle, got behind the wheel, and we were off the hospital. At that point, my body relaxed. I was safe. But it was then that the pain of my broken arm and shattered elbow hit me like nothing I had felt before (transplant included). For the rest of that ambulance ride, I was sucking back on the laughing gas as hard as I could. As August of this year turned into September, I began feeling some semblance of safety. I was starting to take some steps in feeling comfortable with myself, comfortable being alone in the house, and discovering a bit more of who I now was and who I wanted to be. But like being in the back of that ambulance, as I was beginning to feel safer, the pain also began hitting much more powerfully. Kim’s memorial was now less than ten days away, and I knew something was going to happen. I knew it would be incredibly painful and that the shock of spring and summer was thawing. But in the days leading up to Kim’s memorial, I knew that something else was brewing, something I couldn't put into words. I could sense an abyss opening up in front of me. I just didn’t know what it was.  Do you remember the board-game, Snakes and Ladders? It was a simple game where the players would roll the dice and see how many spaces up the switch-backed game board they could go. On some of the squares that the players would land, there would be a picture of a ladder extending up the game board. The player could then move their playing piece up the ladder to whichever square the ladder ended on. Thus, you could be propelled forward anywhere between 10 to 60 spaces. On other squares, however, you could land on the head of a snake, in which case you would slide back down the game board to wherever the snake's tail was, and thus you would lose anywhere between 10 to 60 spaces. I liked playing this game because it was a game of chance, thereby meaning that as the youngest in my family, I had a chance of winning; probably the only game I ever had a chance of beating my older siblings or parents at. Snakes and Ladders is the closest I've come to finding an appropriate metaphor for my journey of grief over Kim’s death. Each morning I wake up, and I wonder what kind of square I will land on that day. Will it be a neutral square where I'll sit where I am, and the day will pass with either a sense of numbness or relative peace? Will it be a day where I will find a "ladder," and I'll feel like I'm making some progress in finding a new normal and some new meaning; an advent of joy perhaps? Or will it be a day where I land on a "snake," find myself once again losing a grip on life, and sliding back into what feels like ever-deepening pits of sorrow and despair. What I’d like to do over the next couple of weeks is begin writing about some of this journey I have been on since Kim passed. As I reflect back over the seven months and two days since Kim died, I can see four or five chapters to this short story. My first blog entry about my journey with grief will be on the shock I experienced throughout the spring and summer. For some reason, I used to think that shock was a bad thing. I’d hear that someone was in shock and believe that it was something they needed to overcome, or maybe it was a sign of weakness. However, I’ve come to see that shock is the natural response of the body to survive a situation that is too painful to experience in full. I can see now how much of the spring and summer were spent in shock, and my body and emotions were taking a bit of a summer holiday from the hard work that it subconsciously knew it would have to do. The second chapter of this mini-series will be on Kim’s memorial. I felt a growing fear and anxiety in the week leading up to it. I felt that something was going to change, but I could not put into words what that was. Then, the Monday morning following her memorial, the realization of what that anxiety was hit me, and it felt like a dark abyss opened up in front of me. The third blog entry, Lord-willing I get there, will be about the ever-deepening darkness and numbness of October, precisely the complicated emotions over finishing up my book, Thanksgiving, and dealing with some challenges and unpredictability related to my health. The fourth entry will have to do with the season I am in right now (hopefully, I will still feel up to writing about this in a week or two). The last two weeks have seen a reprieve of the dark emotions. Some self-realizations during this time have even brought some glimmers of contentment. This all has to do with the little things of life and beginning to take a few tentative steps into the unknown. And lastly, I will give an update on how I am doing when I finish this series. I can’t begin to imagine how I will be feeling at that time, so I’m not even going to try. As I have alluded, I have not written any of these entries yet. I have a sketched outline in my notepad and a couple of quotes I might use, but that is it. I can guarantee you this writing is something I want to do, and I intend to do it, but I don't know whether I can do it. One part of grief is that it is unpredictable. I plan to write two blog posts a week, but I can’t promise that will happen. Part of getting a look into my journey with grief is also having to journey and wait with me. So, if I all of a sudden go silent, you can guess I woke up one morning and stepped on a snake, thus sliding back down into the emotional paralysis of sorrow. On the other hand, if I wake up tomorrow and hit a ladder of excitement, well, then maybe all five entries will come out in one week (I can promise you this won’t happen).

Some of you may not be interested in this, or maybe it won’t be healthy for you to read it, and I understand that. I am doing this more for myself than for the reader, so there is no pressure to read this or follow along. I am putting this out there to document some of what I have been going through, and if there is someone else who is going through a similar kind of loss, then perhaps there is something in my rambling that can help or be a companion for you. I will hopefully see you next week with my first blog entry into this mini-series on my journey with grief.  Tomorrow, Oct 2nd, marks six months since Kim passed away. Most days, I still find myself asking, How did this happen? Of course, I know how it happened in time, we lived every day of it together, but how did life turn out this way? I still have a difficult time believing that Kim is gone.  I think a big part of this, and something I am thankful for, is that the memories I have of Kim are primarily of the good times we had. I don’t know if it is due to trauma, or shock, or just the way our brain and memory works, but the difficult memories, the memories of Kim’s final weeks and months, or all the time we spent in the chemo-clinic or recovering from surgery, are not memories that often come to mind. They are there when I think about them, but the good memories come to mind most naturally. Of lazy nights sitting and watching TV together. Of Kim sitting cross-legged on the couch, puzzle board on her lap, while I read in my chair. Camping at Christina Lake or sitting on the beach in Hawaii. Of making dinner and doing the dishes together, Kim still in her work-sweater and dress pants having just come home from work. These are the memories that come most naturally. But it is these memories that make me wonder over and over, how did this happen? How could that vibrant, beautiful, amazing woman be gone? And yet, she is. This past month has been significant. On the farm, we started and finished corn harvest for another year. We held Kim’s memorial service. And I announced my book project. There have been sparks of joy and excitement, of accomplishment and pride, but the prevailing emotion I find myself experiencing is one of numbness or indifference.  Lament for a Son, Nicholas Wolterstorff Lament for a Son, Nicholas Wolterstorff In his book, Lament for a Son, Nicholas Wolterstorff writes, “The passion is cooled, the striving quieted, the longing stilled. My attachment is loosened ... Instead of rowing, I float. The joy that comes my way I savor. But the seeking, the clutching, the aiming, is gone.” Now this doesn’t mean I don’t laugh, have fun, or get carried away in a good conversation. But once the wake of those moments settle, there is again a sense of emptiness and aimlessness, of "floating." I am getting by. I have a small circle of close friends who keep tabs on me, as well as my amazing family. COVID does make it worse as I really can’t get out much, but I am not alone in that, and I’ve been able to reconnect with the online CF community.  If you want to do something to mark this six-month anniversary of Kim's passing, then all I ask is you take a moment to reflect on Kim and what she meant to you. Raise a glass of your favorite beverage to the unforgettable person she is. As was clear from her memorial, Kim touched so many lives and lived such an authentic life. I am so proud to have been her husband. I miss you, Kim. |

George Keulen's BlogWelcome to my blog. This is a place to find periodic updates on life's ups and downs as I face some old/new health challenges. Some of the updates will be written by me, while others will be updated by my wife, Carrie. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed