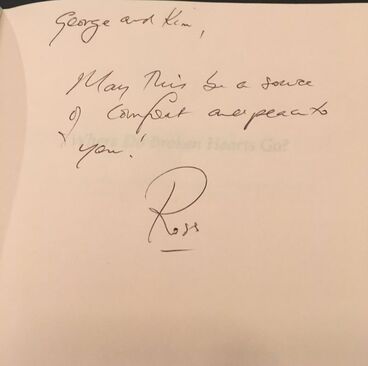

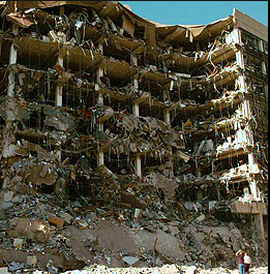

“The reality of grief is far different from what others see from the outside. There is pain in this world that you can’t be cheered of ... Some things cannot be fixed. They can only be carried.” (Megan Devine, It’s OK That You’re Not OK”) As I reflect on the past seven months without Kim, I see that what I might call a “first chapter” of my journey with grief happened during the spring and most of the summer of this year. There are two defining features that I see at play throughout that time. The first was shock; the second was a complete loss of identity. Shock. Back in May 2019, I broke my arm. I was mountain biking in Watershed Park, just minutes from my house. I was riding a downhill trail, one I had done many times before. I came to a tabletop jump whose landing went immediately into a sharp right-handed bend. I hit the jump fine, but in landing, my rear wheel hit the edge of the tabletop, which then ejected my bike forward straight into the high-side of the lefthand berm. My front tire hit this wall of dirt, and my bike and I went flying through the air, wheels over handlebar. While flipping over in the air, I remember thinking, “don’t worry, you’ll be okay, you’ve crashed hard before.” However, when I hit the ground and came to a stop (sitting upright), I noticed that I was covered in blood. I then looked at my right arm and saw that it was bent in a way it was not supposed to ever be bent, and there was a bone sticking out of it. In the three seconds it took to realize how much trouble I was in, I remember thinking, “Please, shock, do what you were made to do!”  Ross Hastings, a professor of mine at Regent College, and whose wife passed away from cancer in 2008, has written a book on grief, Where do Broken Hearts Go? In it, he writes, “For one thing, when a loved one dies, no matter how well prepared we think we are, we shut down in various ways and to different degrees. We are in shock ... Shock, our involuntary defence mechanism, is actually a gift.” Before reading these words in 2016, the same year that Kim was first diagnosed with stage-four colon cancer, I had always thought that shock was a bad thing, that it was somehow an escape from reality. A weakness or something that wasn’t the best way to process or move forward (to be sure, one cannot live in a state of perpetual physical shock; its symptoms can kill a person. When I broke my arm, I experienced many of those symptoms: drop in blood pressure, profuse sweating, skin turning grey or white). But what I didn’t understand before reading this book is that shock is actually a saving grace. Shock is a natural way for the body to survive, for short periods of time, immense life-threatening pain. Back in 2019, sitting beside a tree with a bone sticking out of my arm, shock is what gave me the survival instinct and ability to stand up (albeit on the edge of fainting) and walk/shuffle out of the forest so that the ambulance could pick me up and bring me to the hospital as fast as possible. In the same way, in the immediate days, weeks, and months after Kim passed away, shock was one of the main things that helped me survive what would have been insurmountable emotional pain. Sitting here today, most of the spring and summer is a blur to me. Most of my memories from just a few months ago are swallowed into an indistinguishable mass. There are things I know I did, people I met, family I spent time with, but the details are a fog. Meeting a friend at White Rock beach on several occasions to watch the sun go down and share memories of Kim. Having a close friend come over for drinks to check in on me. Getting together with Kim’s family, where one of Kim’s brothers made all of our drinks a little stronger than usual, thus helping dull the fact that Kim was so painfully missing. And, of course, putting in a lot of time working on the farm. But many of those memories are a blur. What was said, and the number of times they were repeated, is all lost. I was in survival mode. I knew I needed to talk to people, so I sought out friends, or they sought me out. I knew I needed to get out of the house, so I went for drives, walks, bike rides, or sat on the beach. But looking back, it is as if I was on autopilot and I wasn’t taking anything in. I was trying to survive until the following day, just putting in time. The shock prevented the pain of Kim’s absence from reaching the core of my being, but it also stopped everything else in life from penetrating as well. Now don’t get me wrong. In the weeks and months after Kim passed, there were moments of incredible pain. Times where I would be lying face down on the couch, pounding the pillows with everything I had, and expelling groans too deep for words. In those moments, I didn’t know how I was ever going to go on. There were times I wept openly in front of friends and family. Times I felt I couldn’t go on and didn’t want to go on. But despite those moments of complete disorientation, I was also able to function in ways that surprised me. It was as if the shock would let off a pressure release of grief so that I didn’t explode, but it also protected me from feeling the full impact so close to the event.  Kim and I attended Ross' book launch just months after Kim's initial diagnosis. He signed our copy appropriately. Kim and I attended Ross' book launch just months after Kim's initial diagnosis. He signed our copy appropriately. “With shock comes numbness and an unintentional sense of denial. Our minds cannot grasp it. Our emotions are too powerful to be processed at that time. If we did not have defence mechanisms in place, we would not be able to handle the reality of our losses. Their full impact would kill us.” (Ross Hastings, Where do Broken Hearts Go?)  This idea of being in shock was not something I was totally aware of at the time (at least, I don’t think I was). It was not until August began winding down and I entered into some deeper reflection that I realized how much my internal defense mechanisms had protected me during the first four months of being without Kim. Identity The second significant piece of my grief puzzle, however, had to do with my identity. One thing that I did feel within the first weeks after Kim’s passing was a total and complete loss of identity. In being married to Kim, we had created an identity together. We didn’t lose our individual identities to each other, we were still two very different people, but we had also come to create a new identity as one person. With Kim now being gone, it was as if half of me had been torn away. I felt like a building you might see on the news, where half of it has been bombed to rubble, and so each floor of the building ends in midair, and wires and pipes are sticking out into nothing. I felt like my identity had been cut in half, ripped apart. And with this came a total loss of confidence. I think I am a fairly courageous person. Through life experience, I have come to see that there is not a lot in life that we can have control over or hide from, and so it is often better to just hit difficult situations head-on. However, I am not a confident person. Never have been. As a kid, I would always get sick to my stomach before hockey games. I feel I am often timid in social settings where I don’t have a leadership role. But never has my lack of confidence been more acutely felt than now, without Kim. I didn’t realize it until she was gone, but I ran almost everything I did past her. Something as simple as what to wear to church when I was preaching; I would always come downstairs after showering and dressing, stand in front of Kim, and ask, “Is this okay?” Whenever I would purchase something (other than books), I would ask what she thought. We would often go for walks in the evening, sharing about our day, talking through all our decisions in life. I am an over-thinker, and so often, the only way I would make a big decision was when Kim would finally say, “Just do it already.”  With her gone, I now feel paralyzed and panicked. This summer, when I began making final edits and approvals for my book, I broke down. I had no clue if anything I was rewriting was any good, if it made sense, or even fit in my story. I had no clue how to pick the image and design for my front and back cover. I felt hollow. Thankfully, my sister-in-law, Heidi, who has a very keen eye for design and was excited to help with my book, walked me through the final half-year of publishing. I no longer knew who I was, what I liked, or what I wanted. I had lost my identity, I had lost all confidence. The final quote I will use from Ross Hastings' book is this: “I think grief is the process of shock thawing out.” Sitting on the side of 64th Avenue back in May 2019, a truck-load of firefighters standing around me, I knew that my shock was soon going to dissipate. Now that I was out of the woods, first responders present, my body was beginning to feel safer. The paramedics arrived within minutes. They wrapped my arm, got me onto the stretcher, and loaded me into the back of the bus. The driver closed the doors, walked around the side of the vehicle, got behind the wheel, and we were off the hospital. At that point, my body relaxed. I was safe. But it was then that the pain of my broken arm and shattered elbow hit me like nothing I had felt before (transplant included). For the rest of that ambulance ride, I was sucking back on the laughing gas as hard as I could. As August of this year turned into September, I began feeling some semblance of safety. I was starting to take some steps in feeling comfortable with myself, comfortable being alone in the house, and discovering a bit more of who I now was and who I wanted to be. But like being in the back of that ambulance, as I was beginning to feel safer, the pain also began hitting much more powerfully. Kim’s memorial was now less than ten days away, and I knew something was going to happen. I knew it would be incredibly painful and that the shock of spring and summer was thawing. But in the days leading up to Kim’s memorial, I knew that something else was brewing, something I couldn't put into words. I could sense an abyss opening up in front of me. I just didn’t know what it was.

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

George Keulen's BlogWelcome to my blog. This is a place to find periodic updates on life's ups and downs as I face some old/new health challenges. Some of the updates will be written by me, while others will be updated by my wife, Carrie. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed